You likely don’t think about the pink fluff or rigid foam hiding behind your walls until something goes wrong. Maybe you feel a cold draft while watching TV in January, or perhaps your upstairs bedrooms stay unbearably hot in July, even though your air conditioner runs constantly. These discomforts are rarely the fault of your HVAC system alone. They usually point to a failure in your home’s thermal envelope.

Insulation is the silent workhorse of any residential structure. It dictates comfort, controls energy bills, and protects the structural integrity of the house by managing moisture. Yet, for many homeowners, the topic remains confusing. The market is flooded with terminology, R-values, thermal bridging, vapor retarders, and a vast array of material options that vary wildly in price and performance.

This guide serves as a complete resource for understanding residential insulation. We are not just looking at what to buy; we are examining how these systems work, where they belong, and how to make choices that pay off for decades. Whether you are building a custom home or retrofitting a drafty 1970s split-level, the principles remain the same.

You will learn the building science of heat flow, receive an honest breakdown of material options without the marketing spin, and understand the installation strategies that set a high-performing home apart from a mediocre one.

To make an informed choice, you must first understand the problem you are solving. Insulation does not actually “add” heat or cold. It slows the movement of heat. In the winter, heat wants to escape to the cold outdoors. In the summer, outside heat tries to force its way into your cool interior.

Heat moves in three specific ways, and your insulation strategy must address all of them:

Most standard insulation materials primarily target conduction. They trap pockets of air (which is a poor conductor) within a matrix of fibers or foam. However, if you ignore air leaks (convection), the best insulation in the world will fail to perform.

You will see “R-value” printed on every bag of insulation. This number measures thermal resistance. The higher the R-value, the better the material resists heat flow.

However, R-value is not the only metric that matters. A study from the Building Science Corporation explains that nominal R-values are measured in a lab with zero wind or air pressure. In the real world, if wind blows through your insulation (familiar with loose fiberglass), the effective R-value drops significantly.

Key Concept: Don’t just chase the highest number. A properly installed R-15 wall often outperforms a poorly installed R-20 wall because gaps and compression ruin performance.

Expert Tip: R-value is cumulative but follows the law of diminishing returns. Tripling your attic insulation won’t triple your savings. There is a “sweet spot” based on your climate zone where the cost of adding more insulation no longer pays for itself in energy savings.

The “best” insulation depends entirely on where you are putting it and your budget. High Country Solutions has seen every material type in action, and we know that each has a specific role to play.

This is the industry standard. It consists of spun glass fibers that trap air.

Made primarily from recycled newsprint treated with fire-retardants (usually borates), cellulose is a favorite among eco-conscious builders.

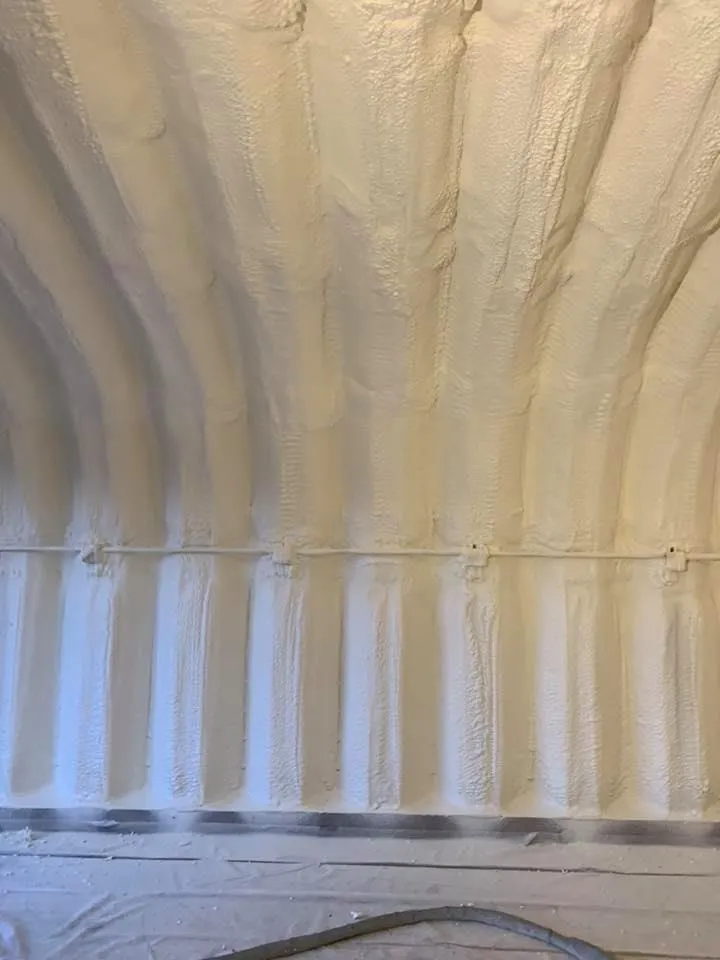

Spray foam is a chemical mixture that expands and hardens. It is often considered the gold standard for performance, but it comes with a premium price tag.

Open-Cell Foam:

Closed-Cell Foam:

Made from spun rock or slag, this material is denser than fiberglass.

These are stiff boards of insulation.

| Material | Approx R-Value per Inch | Air Sealing Ability | DIY Friendly? | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiberglass Batt | 3.1 – 3.4 | Poor | High | Low |

| Blown Cellulose | 3.2 – 3.8 | Moderate | Moderate | Low-Mid |

| Open-Cell Foam | 3.5 – 3.7 | Excellent | No | Mid-High |

| Closed-Cell Foam | 6.0 – 7.0 | Superior | No | High |

| Mineral Wool | 4.0 – 4.2 | Poor | High | Mid |

| Rigid Foam (XPS) | 5.0 | Excellent (if taped) | Moderate | Mid |

Knowing the materials is half the battle. Knowing where to apply them is the other half. An effective thermal envelope is continuous; imagine wearing a down jacket but leaving the zipper open. That is what happens when you miss key areas.

According to data published by the Department of Energy, a properly insulated attic can reduce your heating bill by 10 to 50 percent. Heat rises, and in winter, your attic is the primary escape route for the warmth you pay for.

Insulating walls is trickier because of wires, pipes, and outlets.

These are moisture-prone areas. Using fiberglass here is often a mistake because it acts like a sponge for mold.

Key Takeaway: The effectiveness of your insulation is limited by the quality of your air barrier. An R-60 attic with unsealed can lights is essentially a chimney sucking heat out of your house. Always seal before you insulate.

Modern homeowners are increasingly concerned about indoor air quality (IAQ). Insulation plays a massive role here.

Some synthetic insulations release Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) as they cure. Spray foam is the most common culprit. While safe when installed correctly, it requires a strict ventilation period (usually 24 to 48 hours) during which the house must be vacated.

If chemical sensitivity is a concern, materials like mineral wool or formaldehyde-free fiberglass are safer bets. Sheep’s wool insulation is also emerging as a natural niche product, though it comes at a premium.

Your walls need to breathe not air, but vapor. If you create a vapor barrier on both sides of a wall (like vinyl wallpaper on the inside and plastic wrap on the outside), moisture gets trapped in the middle. Rot follows.

A report from the Building Performance Institute highlights that understanding local climate zones is vital. In cold climates, the vapor retarder is typically applied to the warm (interior) side. In hot, humid climates, it is often better to avoid interior vapor barriers entirely, allowing the AC to pull moisture out of the wall assembly.

Is it worth spending $5,000 to re-insulate an attic? Usually, yes, but the timeline for Return on Investment (ROI) varies.

You should look at payback in two ways:

Governments and utility companies want you to reduce load on the grid.

Even with the best materials, things go wrong. Here are the hurdles High Country Solutions sees most often in the field.

Stuffing an R-19 fiberglass batt into a 3.5-inch wall cavity (meant for R-13) does not give you R-19. It compresses the pockets of air, actually reducing the performance. Insulation needs to be lofty, not packed tight (unless it is specifically designed dense-pack cellulose).

Old recessed lights (can lights) get very hot. If you pile insulation over them, you risk a fire. You must either use “IC-rated” (Insulation Contact) fixtures or build a box around the light to keep insulation away.

The attic access hatch is a giant hole in your ceiling. If you insulate the entire attic but leave the hatch as a thin piece of plywood, you create a massive thermal bridge. The hatch should be insulated to the same R-value as the rest of the attic and weather-stripped to stop air leaks.

You can’t see heat loss with the naked eye, but you can measure it.

This is a diagnostic tool used by professionals. A powerful fan is mounted in an exterior door frame to pull air out of the house, lowering the indoor air pressure. Higher outside air pressure then flows in through all unsealed cracks and openings. This quantifies exactly how “leaky” your home is.

Using an infrared camera, an auditor can see cold spots in your walls and ceilings. This acts like an X-ray for insulation, revealing settled cellulose or missed batts without opening the wall.

The industry is moving toward “Passive House” standards, where insulation is so effective that conventional heating systems are barely needed.

You can do a quick check in the attic. If your insulation is level with or below your floor joists (so you can see the wood beams), you likely need more insulation. The Department of Energy generally recommends R-38 to R-60 for attics in most climates, which translates to 12-18 inches of depth depending on the material.

Generally, yes. Unless the old insulation is wet, moldy, or contaminated with rodent droppings, you can layer new material right on top. In fact, laying new batts perpendicular to the joists over old insulation helps cover the wood thermal bridges.

Yes, when applied correctly by certified professionals. The issues with spray foam usually stem from improper mixing ratios or from using it too thick or too fast, which generates excessive heat. Once fully cured (usually 24-48 hours), high-quality spray foam is inert and does not release harmful gases.

Faced insulation has a paper or foil vapor retarder on one side. Unfaced has no covering. Faced batts are used in first-time applications (like new walls) to control moisture. Unfaced batts are used when adding insulation over existing layers, as you never want to trap moisture between two vapor barriers.

Thermal insulation helps, but it isn’t soundproofing. While materials like mineral wool and open-cell foam absorb sound, proper soundproofing requires “decoupling” the wall (separating the drywall from the studs) and adding mass. Insulation will muffle voice frequencies, but won’t stop the bass from a subwoofer.

Most insulation materials are designed to last the life of the building (50+ years). However, fiberglass can sag, and cellulose can settle over 15-20 years, requiring a “top-up.” Spray foam and rigid foam are virtually permanent unless physically damaged.

Improving your home’s insulation is one of the few home projects that pays you back every single month. It transforms your house from a passive structure that bleeds energy into an efficient system that retains comfort.

Start with an audit. Go into your attic and basement. Look for the black stains on insulation that indicate air leaks. Check the depth of your attic fill. Identify the cold rooms in your house. Once you have a clear picture of the deficiencies, prioritize air sealing, then tackle the attic, followed by the basement or crawlspace.

Don’t let the technical jargon paralyze you. The goal is simple: keep the conditioned air in and the unconditioned air out. Whether you choose the DIY route with fiberglass or invest in professional spray foam, the attention to detail, sealing gaps, avoiding compression, and ensuring continuous coverage matters more than the brand name on the package.

If the thought of crawling through a dusty attic or calculating R-values feels overwhelming, you don’t have to do it alone. High Country Solutions is here to help you navigate these choices. We can assess your current setup and design a plan that fits your budget and comfort goals.

Contact High Country Solutions